Amazing Human Organ Newly Discovered

Researchers have identified a previously unknown feature of human anatomy with implications for the function of all organs, most tissues and the mechanisms of most major diseases.

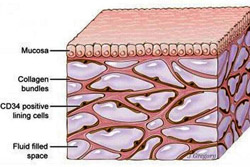

Published March 27 in Scientific Reports, a new study co-led by an NYU School of Medicine pathologist reveals that layers of the body long thought to be dense, connective tissues below the skin’s surface, lining the digestive tract, lungs and urinary systems, and surrounding arteries, veins, and the fascia between muscles are instead interconnected, fluid-filled compartments.

This series of spaces, supported by a meshwork of strong (collagen) and flexible (elastin) connective tissue proteins, may act like shock absorbers that keep tissues from tearing as organs, muscles, and vessels squeeze, pump, and pulse as part of daily function.

Importantly, the finding that this layer is a highway of moving fluid may explain why cancer that invades it becomes much more likely to spread. Draining into the lymphatic system, the newfound network is the source of lymph, the fluid vital to the functioning of immune cells that generate inflammation. Furthermore, the cells that reside in the space, and collagen bundles they line, change with age, and may contribute to the wrinkling of skin, the stiffening of limbs, and the progression of fibrotic, sclerotic and inflammatory diseases.

The field has long known that more than half the fluid in the body resides within cells, and about a seventh inside the heart, blood vessels, lymph nodes, and lymph vessels. The remaining fluid is “interstitial,” and the current study is the first to define the interstitium as an organ in its own right, and as one of the largest of the body, say the authors.

The researchers say that no one saw these spaces before because of the medical field’s dependence on the examination of fixed tissue on microscope slides, believed to offer the most accurate view of biological reality. Scientists prepare tissue this examination by treating it with chemicals, slicing it thinly, and dying it to highlight key features. The “fixing” process makes vivid details of cells and structures, but drains away any fluid. The current research team found that the removal of fluid as slides are made causes the connective protein meshwork surrounding once fluid-filled compartments to pancake, like the floors of a collapsed building.

“This fixation artifact of collapse has made a fluid-filled tissue type throughout the body appear solid in biopsy slides for decades, and our results correct for this to expand the anatomy of most tissues,” says co-senior author Neil Theise, MD, professor in the Department of Pathology at NYU Langone Health. “This finding has potential to drive dramatic advances in medicine, including the possibility that the direct sampling of interstitial fluid may become a powerful diagnostic tool.”

The study findings are based on newer technology called probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy, which combines the slender camera-toting probe traditionally snaked down the throat to view the insides of organs (an endoscope) with a laser that lights up tissues, and sensors that analyze the reflected fluorescent patterns. It offers a microscopic view of living tissues instead of fixed ones.

Using this technology in the fall of 2015 at Beth Israel Medical Center, endoscopists and study co-authors David Carr-Locke, MD, and Petros Benias, MD, saw something strange while probing a patient’s bile duct for cancer spread. It was a series of interconnected cavities in this submucosal tissue level that not match any known anatomy.

Faced with a mystery, the endoscopists walked the images into the office of their partnering pathologist in Theise. Strangely, when Theise made biopsy slides out of the same tissue, the reticular pattern found by endomicroscopy disappeared. The team would later confirm that very thin spaces seen in biopsy slides, traditionally dismissed as tears in the tissue, were instead the remnants of collapsed, previously fluid-filled compartments.

For the current study, the team collected tissue specimens of bile ducts during twelve cancer surgeries that were removing the pancreas and the bile duct. Minutes prior to clamping off blood flow to the target tissue, patients underwent confocal microscopy for live tissue imaging.

Once the team recognized this new space in images of bile ducts, they quickly recognized it throughout the body, wherever tissues moved or were compressed by force. The cells lining the space are also unusual, perhaps responsible for creating the supporting collagen bundles around them, say the authors. The cells may also be mesenchymal stem cells, says Theise, which are known to be capable of contributing to the formation of scar tissue seen in inflammatory diseases. Lastly, the protein bundles seen in the space are likely to generate electrical current as they bend with the movements of organs and muscles, and may play a role in techniques like acupuncture, he says.

Reference: Petros C. Benias, Rebecca G. Wells, Bridget Sackey-Aboagye, Heather Klavan, Jason Reidy, Darren Buonocore, Markus Miranda, Susan Kornacki, Michael Wayne, David L. Carr-Locke, Neil D. Theise. Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Scientific Reports, 2018; 8 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-23062-6